Blackbody Radiation and the Quantum Revolution

Introduction: A Tangled Dialogue Between Math and Physics

The study of blackbody radiation is one of the most striking cases in the history of science. It shows that mathematics is not merely a descriptive tool but a critical lens capable of challenging physical theories. By the late 19th century, it was a formula that “screamed”: something wasn’t adding up. Classical physics predicted an absurd outcome (infinite energy), and mathematics hinted at the need for a conceptual leap: quantization.

Science, in this sense, advances not only by observing the world but also by observing its own equations. The case of blackbody radiation highlights the deep interconnection between mathematics and physics—no hierarchy, just a continuous dialogue where abstraction guides, challenges, and sharpens physical understanding.

Radiation and Early Empirical Observations

When a body is heated, internal electric dipole vibrations emit electromagnetic radiation. As early as the late 1700s, it was observed that during porcelain firing, different materials glowed red at the same temperature, regardless of their chemical composition.

By the mid-1800s, spectroscopic studies revealed:

- Hot solids or liquids emit a continuous spectrum;

- Hot rarefied gases emit line spectra.

🔍 A spectrum is a body’s “light signature.” Solids glow across all frequencies (like glowing metal), while gases emit only specific ones (like neon lights).

Imagine an orchestra playing a warm tone. Some instruments emit low notes (low frequencies), others high (high frequencies). The total sound is complex—just like the radiation from a hot body, composed of multiple frequencies, each carrying a certain amount of energy.

Energy distribution indicates how much energy exists at each frequency:

- At low temperature, most energy lies in the infrared (heat).

- At higher temperatures, visible frequencies (red, yellow, white) also gain intensity.

Energy Density and Spectral Distribution

We define the energy density per unit volume as:

\[u(\vec{r}) = \frac{d\varepsilon}{d\tau} \quad \left[ \frac{J}{m^3} \right]\]where \(\vec{r}\) is spatial position. The function \(u(\vec{r})\) tells how much energy is contained in a specific cavity point.

The spectral energy density is:

\[\rho(\nu) = \frac{du}{d\nu} \quad \left[ \frac{J}{m^3 \cdot \text{Hz}} \right]\]Thus, the energy between \(\nu\) and \(\nu + d\nu\) is:

\[du = \rho(\nu) \, d\nu\]Integrating over all frequencies gives the total energy per volume:

\[u = \int_0^{+\infty} \rho(\nu) \, d\nu\]🔍 \(\rho(\nu)\) shows how energy is spread across frequencies. The higher \(\rho(\nu)\), the more intense the emission at that frequency.

🔹 Think of the spectrum as a bar chart—each bar is a frequency, and its height is the energy there. \(\rho(\nu)\) is the curve connecting the bar peaks.

Kirchhoff and the Ideal Blackbody

A blackbody, theorized by Gustav Kirchhoff in 1859, is an ideal object that absorbs all incoming electromagnetic radiation—no reflection, no transmission. Thermodynamic symmetry implies it must also emit perfectly.

Kirchhoff showed that, in thermal equilibrium, the ratio between emitted and absorbed power at a given frequency depends only on frequency and temperature. This function is universal—it applies to all blackbodies, regardless of shape or material.

🔍 If an object absorbs well at a certain frequency, it must emit equally well at that frequency. Otherwise, one could build a machine that violates the second law of thermodynamics by transferring heat between bodies at the same temperature.

To physically model this, Kirchhoff imagined a cavity with adiabatic walls and a tiny hole. A ray of light entering the hole bounces many times until it’s absorbed. Escaping radiation from the hole represents the ideal blackbody spectrum.

\[\frac{E_\nu}{A_\nu} = J(\nu, T)\]Blackbody Spectrum and Wavelength

Besides frequency \(\nu\), the spectrum can also be described via wavelength \(\lambda\), where \(\nu = \frac{c}{\lambda}\).

Then:

\[du = \rho(\lambda) \, d\lambda\]🔍 It’s often more intuitive to use wavelength: red light ≈ 700 nm, blue light ≈ 450 nm.

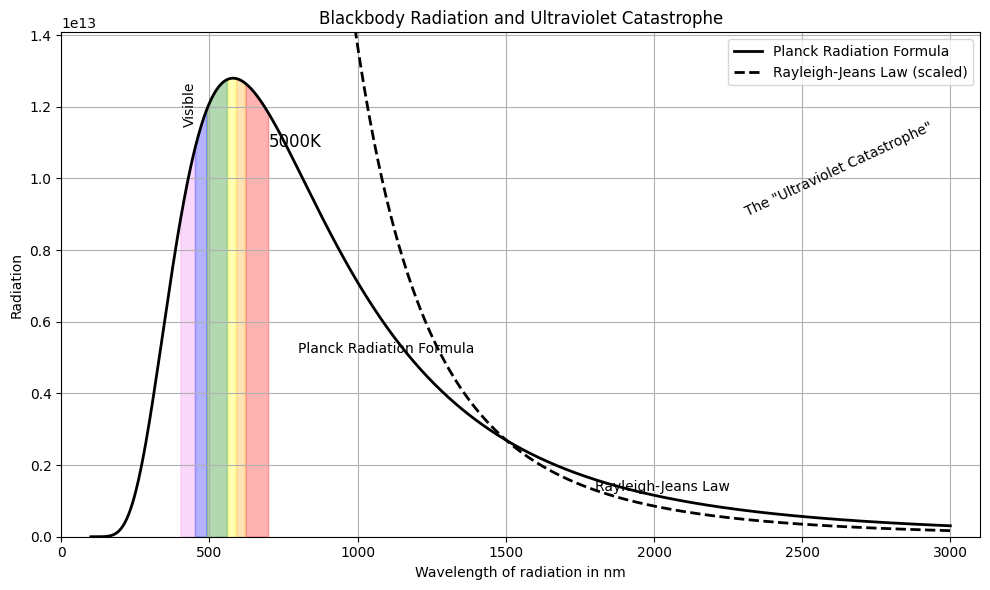

The graph of \(\rho(\lambda)\) has a bell-shaped curve, peaking at shorter wavelengths as temperature increases.

📌 This peak will be the subject of Wien’s displacement law.

Wien’s Law and Total Emitted Energy

In 1893, Wien proposed a spectral form:

\[\rho(\nu) = \nu^3 F\left( \frac{\nu}{T} \right)\]This means temperature dependence appears in the ratio \(\nu/T\).

🔍 Changing temperature shifts and stretches the spectrum without altering its shape.

Integrating \(\rho(\nu)\):

\[u = \int_0^{+\infty} \rho(\nu) \, d\nu = \sigma T^4\]\(\sigma\) is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant.

📌 The total emitted energy grows with the fourth power of temperature—a core thermodynamic law.

Wien’s Displacement Law

The spectrum’s peak occurs when:

\[\frac{d\rho}{d\nu} = 0 \quad \Rightarrow \quad \lambda_{\text{max}} T = b\]where \(b\) is a constant.

📌 The hotter a body, the shorter the peak wavelength—explaining the red-to-white glow of heated metals.

Classical Prediction: Rayleigh–Jeans Law

With classical assumptions, the energy density is:

\[\rho(\nu) = \frac{8\pi \nu^2 kT}{c^3}\]📌 This works for low frequencies but diverges as \(\nu \to \infty\): the “ultraviolet catastrophe.”

📊 The graph shows how classical predictions (Rayleigh–Jeans) diverge at high frequencies, while Planck’s quantum model fits the experimental data across the spectrum.

Oscillators and Planck’s Insight

🔍 Why oscillators?

To model emission, Planck proposed microscopic systems inside cavity walls that exchange energy with the EM field. These weren’t literal springs, but abstract oscillators—ideal systems that vibrate at certain frequencies.

It’s a model, not a physical description, linking frequency and energy exchange.

Planck’s Solution

In 1900, Planck proposed that energy exchange is discrete:

\[E = n h \nu, \quad n = 0, 1, 2, \dots\]Where:

- \(h\) is Planck’s constant;

- \(\nu\) is frequency.

📌 Planck quantized the energy of oscillators, not the field. Each can exchange energy only in units of \(h\nu\).

Using Boltzmann statistics, Planck derived:

\[\rho(\nu) = \frac{8\pi h \nu^3}{c^3} \cdot \frac{1}{e^{h\nu/kT} - 1}\]🔍 This matches:

- Rayleigh–Jeans at \(\nu \ll kT/h\)

- Wien’s law at \(\nu \gg kT/h\)

- Experiments across all frequencies

📌 This marks the birth of quantum mechanics, with \(h = 6.626 \times 10^{-34}\, \text{Js}\)

Final Reflection: Math, Physics, and Paradigm Shifts

Blackbody radiation reveals the essential role of mathematics in science. Classical theory, supported by principles like energy equipartition, seemed solid—until predictions clashed with experiments.

📌 Here, math doesn’t just describe: it interrogates. Equations highlight inconsistencies and inspire new ideas. Abstraction led the way.

Planck’s quantum step didn’t come from experiment, but from a formal need to fix a divergence. It triggered a revolution: quantum mechanics.

🔍 The blackbody crisis shows how scientific theories, though coherent, are fragile. When one part fails, the whole structure shakes—and a new language is needed to rebuild understanding.

Appendix: Mathematical Derivation of Planck’s Law

Planck assumed discrete energy levels:

\[E_n = n h \nu, \quad n = 0, 1, 2, \dots\]Using Boltzmann statistics, average energy is:

\[\bar{E} = \frac{\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} n h \nu \cdot e^{-n h \nu / kT}}{\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} e^{-n h \nu / kT}} = \frac{h \nu}{e^{h \nu / kT} - 1}\]Number of modes per unit volume in \([\nu, \nu + d\nu]\):

\[dN = \frac{8\pi \nu^2}{c^3} d\nu\]Spectral energy density:

\[\rho(\nu) = \frac{8\pi \nu^2}{c^3} \cdot \bar{E} = \frac{8\pi h \nu^3}{c^3} \cdot \frac{1}{e^{h\nu/kT} - 1}\]Classical Limits

If \(h\nu \gg kT\):

\[\frac{1}{e^{h\nu/kT} - 1} \approx e^{-h\nu/kT} \Rightarrow \rho(\nu) \approx \frac{8\pi h \nu^3}{c^3} e^{-h\nu/kT}\]→ Wien’s Law

If \(h\nu \ll kT\):

\[e^{h\nu/kT} \approx 1 + \frac{h\nu}{kT} \Rightarrow \frac{1}{e^{h\nu/kT} - 1} \approx \frac{kT}{h\nu} \Rightarrow \rho(\nu) \approx \frac{8\pi \nu^2 kT}{c^3}\]→ Rayleigh–Jeans Law